Crowdfunding for Private Security in Oakland Ignores a Few Key Facts

This was originally posted on Policymic and is reposted with permission from the author.

May 8 this past summer, I was in a meeting with the Oakland Police Department discussing new strategies for combating rising crime rates, when we learned that Police Chief Howard Jordan had resigned for medical reasons; Deputy Chief Anthony Toribio was appointed as interim chief. We returned to the east coast on May 9, and by May 10 Toribio had also resigned. In less than three days, the city had two police chiefs quit. Clearly, Oakland is in a spot of trouble.

Besides having problems keeping someone in the police chief’s office, Oakland also suffers from a chronic lack of officers on the streets, which is a likely reason for why Oakland, unlike most of the rest of the country, is experiencing rising crime rates. In response to this, some Oakland residents have taken their security into their own hands, but not as vigilantes. Instead, some residents have hired private security firms to police their neighborhoods, and some have even used Crowdtilt, a crowdfunding website, to raise the funds to pay said firms by pooling funds from community residents.

Considering that the average home price in Oakland’s Rockridge neighborhood — where these crowdfunded initiatives are based — is over $1 million dollars, however, it’s unlikely that these areas are the ones that are really in need of additional security. And while people should be allowed to hire private security, I suspect this strategy is nothing more than a balm to soothe nerves turned jittery by publicized crime rates.

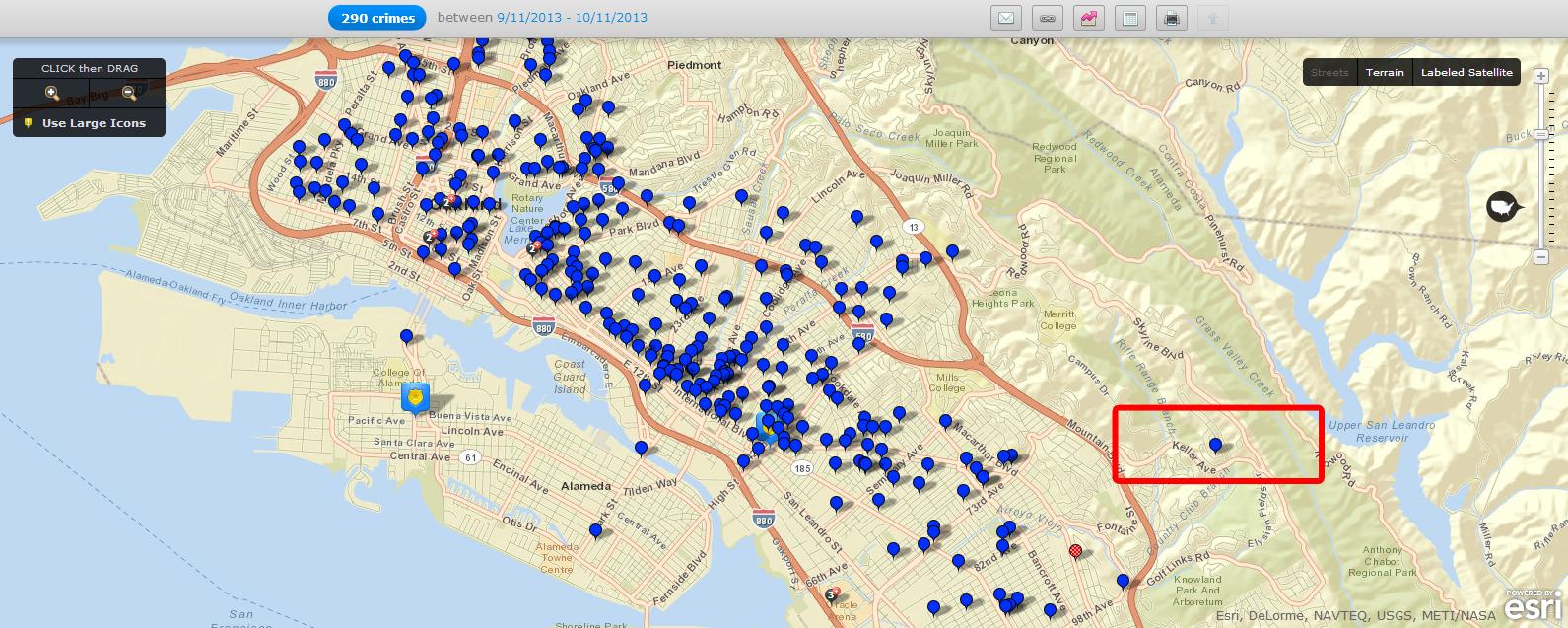

Take the image below. I used the crime mapping software on CrimeMapping.com to see the spatial distribution of robberies and homicides in Oakland from September 2013 to now. (Note: the single month date range and only two offense types were used because the site can only display 800 crime events at a time.) As you can see, the vast majority of the 290 total robberies and homicides occurred in the area west of Highway 280, which is closer to the urbanized, lower socioeconomic areas of Oakland. The area marked by the red rectangle, a neighborhood called Sequoyah Hills, is on the opposite side of Highway 280, and is one of several neighborhoods around Oakland now employing private security.

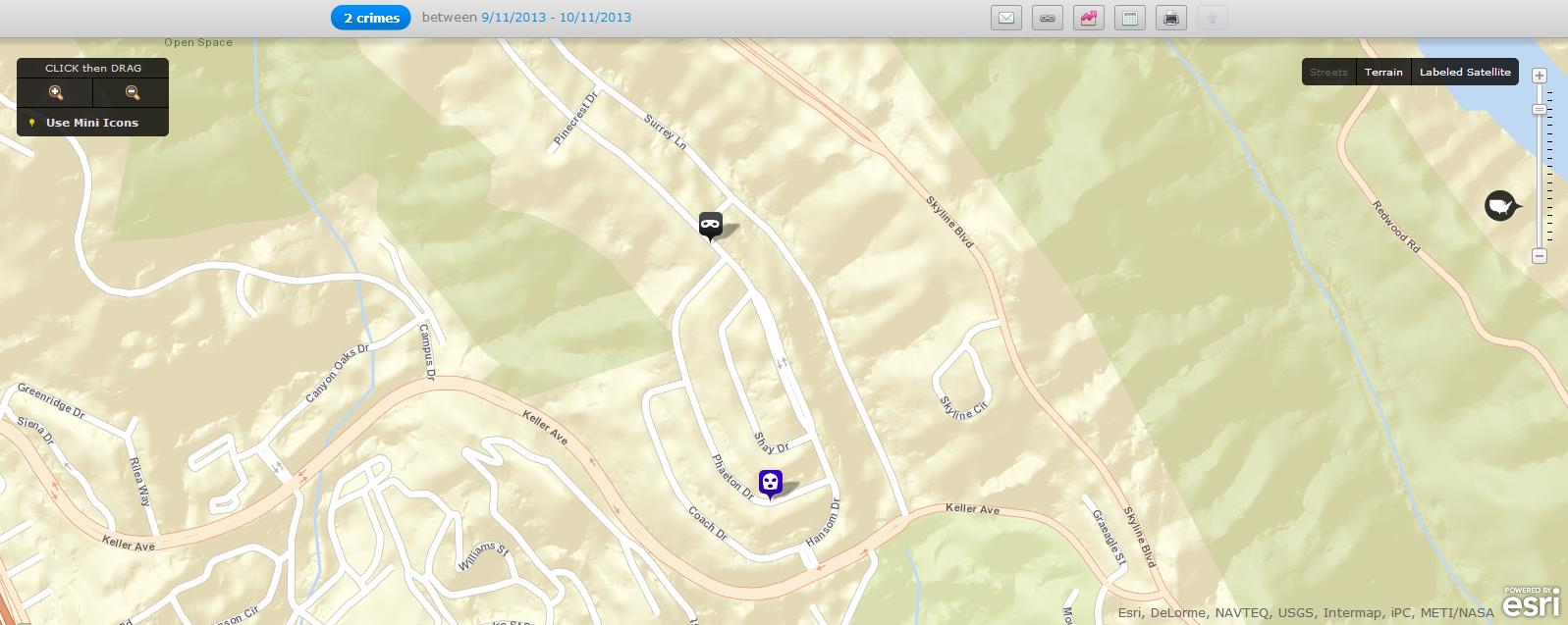

Sequoyah Hills is shown in more detail in the image below. As you can see, it looks a little different than the previous map.

To be sure, a robbery and a burglary in this neighborhood (I added the burglary measure in for this map) is concerning, especially for the residents that live there. But this pattern of extremely localized crime is not unique to Oakland. As in cities across the U.S., crime (and especially violent crime) is concentrated not just in particular neighborhoods, but in particular places within these neighborhoods. It’s these violent micro-places within neighborhoods that could most benefit from additional security, not the ones with a fancy website that are a 3 minute drive from a country club (which also has a nice website).

Still, what’s the harm of crowdfunded security? It’s not your or my tax dollars funding these security firms, and these areas are likely going to stay as safe as they always have been. MIT media scholar Ethan Zuckerman warns, however, that crowdfunding a public service like security has the potential to set a precedent for placing the burden of public goods on the shoulders of the public. If privatized security proves to be a highly effective for reducing crime (which will be difficult to tell because these firms are being employed in low-crime neighborhoods), then the argument could be made for “a government small enough to drown in a bathtub, with services provided by the free market and by crowdfunding a thousand points of light.”

Further, crowdfunded initiatives have the potential to increase inequality. “Unless done very carefully, crowdfunding a city’s project is likely to favor wealthy neighborhoods over poor ones. People in poorer neighborhoods have less to spend on crowdfunding projects, and are less likely to have internet access,” says Zuckerman. Though it’s not the city looking to crowdfund security, the situation in Oakland looks to in some ways fulfill this prediction: It’s the more wealthy parts of the city that are getting private security, not poorer areas like West Oakland that are in dire need of more help with public safety.

To be sure, crowdfunded projects can be a powerful source for good, too. This requires that crowdfunded initiatives be undertaken with an eye towards being incorporated into a larger, city-wide strategy, not one that operates only at the individual neighborhood-level. Further, it is imperative that crowdfunded projects act not as replacements for government services, but instead as supplements. The idea is not to replace police, or other government employees, but instead provide them with support through things like additional manpower or publicly-raised funds.

Neither I nor anyone else is trying to deny people private security. Instead, it’s important to recognize that a neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach to bolstering security through private means is a potentially problematic strategy that is likely to leave the places that are in the most dire situations no safer. While crowdfunding certainly holds promise for harnessing the power of collective efficacy to improve the public good, it is vital that we remain cautious of such efforts’ potential for increasing inequality, as well as for ultimately ignoring the places most in need of help.

Michael Sierra-Arevalo is a doctoral student in the department of sociology at Yale University, and a Graduate Affiliate at the Institution for Social and Policy Studies.