Care 4 Kids? Connecticut’s Struggling Childcare System Provides Critical Perspective on President-elect Trump’s Social Policy Agenda

(December 10, 2016)

Mothers are now primary breadwinners in 40% of American households with children. Yet our policies for working families remain “stuck in the past,” as candidate Trump put it last September; “We need working mothers to be fairly compensated for their work, and to have access to affordable, quality child care for their kids.”

After decades of increasing labor force participation among mothers, one in four American families still spends more than 10% of total income on childcare, with annual day care costs in excess of public university tuition in 31 states. Given such a broad-based constituency of hard working parents, efforts by both major party presidential campaigns to pique voter interest in accessible and affordable childcare seem straightforward. The President-elect’s plan to voucherize K-12 public education, on the other hand, looks quite curious.

All families need access to reliable care options for children too young to begin public school, yet only a subset of America’s poorest workers receive vouchers toward this end.

While universal K-12 eliminates the issue for working parents once children turn five, the incoming Administration hopes to end public education as we know it.

At this puzzling moment in social policy politics, specific imperfections with Connecticut’s childcare status quo – a noncompetitive market reliant on politically-vulnerable public subsidies like the Care4Kids voucher program – provide critical insight into a fundamental misdiagnosis as well as promising developments in President-elect Trump’s Child Care Reforms That Will Make America Great Again. Notwithstanding important differences across social policy domains, political perspective gleaned from the case of childcare has broader implications for emergent discussions of privatizing as-yet-unvoucherized federal programs, such as public school and Medicare.

Much like the plan Secretary Clinton campaigned on, and proposals floated by DC think tanks from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) to the Center for American Progress (CAP), Donald Trump’s solution to America’s childcare crisis continues the course, placing primary emphasis upon boosting the consumption of private childcare services most families struggle to afford. In this sense, the status quo and broader tax breaks proposed by Mr. Trump are only different in degree, both premised on the standard assumption that an adequate supply of attractive childcare options will follow. The data on childcare access in the United States provides little support for this faith in the market mechanism. Twenty years of experience with childcare vouchers for low income working parents suggest that public subsidies for select families have been far from sufficient to overcome inefficiencies inherent to the private delivery of high quality childcare.

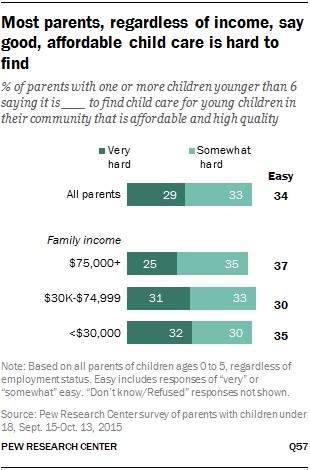

Research from DataHaven on childcare accesibility in New Haven provides community-level evidence of failures consistent with recent national findings on Americans’ frustrations with care options for their children. Counter to expectations of a healthy market, New Haven families face a critical undersupply of infant and toddler care. Affordability is an issue for many families, given a sufficient number of subsidized slots and vouchers for only three in ten of New Haven’s infants and toddlers in low income working families. But childcare availability is a distinct and prior obstacle for all parents, with the total care supplied at any cost enough to cover only 19% of 0-2 year olds in Greater New Haven. Suboptimal supply of private childcare, as experienced in New Haven, provides a plausible foundation for Pew’s “striking” 2015 survey results. Most Americans with young children report difficulty finding “affordable, high quality child care in their community,” with “few differences among parents from different races, income groups or educational backgrounds.”

Research from DataHaven on childcare accesibility in New Haven provides community-level evidence of failures consistent with recent national findings on Americans’ frustrations with care options for their children. Counter to expectations of a healthy market, New Haven families face a critical undersupply of infant and toddler care. Affordability is an issue for many families, given a sufficient number of subsidized slots and vouchers for only three in ten of New Haven’s infants and toddlers in low income working families. But childcare availability is a distinct and prior obstacle for all parents, with the total care supplied at any cost enough to cover only 19% of 0-2 year olds in Greater New Haven. Suboptimal supply of private childcare, as experienced in New Haven, provides a plausible foundation for Pew’s “striking” 2015 survey results. Most Americans with young children report difficulty finding “affordable, high quality child care in their community,” with “few differences among parents from different races, income groups or educational backgrounds.”

Separate from these issues of market malfunction, recent Care4Kids cutbacks in the deep-blue but budget-strapped State of Connecticut reveal political flaws with the voucher as a policy mechanism for fighting poverty and spurring high quality social services provision. In the wake of Congress’ first-ever update to childcare voucher quality controls with reauthorization of the Child Care and Dependent Block Grant in 2014, Connecticut lawmakers have blamed insurmountable federal compliance costs for a series of draconian Care4Kids eligibility changes. Expanding upon October’s closure of Care4Kids for regular priority applicants, working families with income below 50% of the state median, Connecticut’s Office of Early Childhood recently announced that families to-date classified as top priority for childcare subsidies, families headed by former TANF recipients and teen mothers completing high school, will no longer be eligible to apply for Care4Kids at the end of this month.

An example of what political scientists call policy conversion, these internal rules changes amount to outright transformation in the ground-level function of the program. Intended as a critical work-support to keep families off cash assistance, Connecticut has converted Care4Kids into a subsidy attached to particular poor children until they age out of eligibility. The lump transfer of federal funds and governing discretion which characterize block grants has thus provided not only practical means but, at least as important for Connecticut officials, political cover. In the state distinguished first-runner up for the nation’s worst income inequality, the ability to blame Congress is apparently sufficient for lawmakers to balance the budget on the backs of poor children without fear for backlash from the liberal electorate. Combined with high levels of state discretion, the relatively weak support coalition of low income women and their advocates underscores the particular vulnerability of voucher programs as antipoverty policy to the kind of conversion witnessed in Care4Kids. Fortunately, a remedy for this political weakness coincides with the solution to childcare market failures outlined above. An enhanced emphasis on the supply-side in childcare policy would encourage greater provision of services in a market plagued by undersupply, while broadening the basis of political support for the program.

To be sure, universal and free public childcare akin to our current K-12 system is quite unlikely, particularly with unified-Republican government on the horizon. However, current successes in employer-sponsored and community-based efforts to increase childcare availability shine light on significant potential for public policy to leverage these approaches. As the largest employer sponsored childcare system in the country, the Department of Defense’s successful program provides ample inspiration with which the incoming administration might flesh out the barebones section on leveraging employers’ interests in Trump’s childcare plan. At the community-level, the New Haven based organization All Our Kin has demonstrated remarkable potential to increase the net availability of childcare services in a community through targeted professional development and networking opportunities for the owners of small home-based childcare businesses, known as Family Child Care providers.

The presidential inauguration of a (wealthy white male) Republican who ran on the issue of childcare reform should inspire hope among proponents of policy change. But inefficiencies in our current childcare markets suggest that a continued federal focus on inflating demand is misguided – unless coupled with public policies and investment to enhance the quantity and quality of childcare. Several supply-oriented provisions in Trump’s plan deserve praise and serious public consideration; efforts to incentivize employer-sponsored support are particularly promising, as only about one in ten civilian workers eligible for childcare benefits from their places of work. Portending unique prowess for the bully pulpit, the President-elect has already reversed the course of offshoring corporations and moved stock prices with little more than 140 characters. If he can save American’s manufacturing jobs, certainly @realDonaldTrump can convince more companies to help hardworking parents properly care for kids.

Sophie Jacobson is a PhD student in political science and an ISPS Graduate Policy Fellow focusing on the politics of inequality in the United States. Her research centers on American social policy, incorporating historical institutionalist and comparative political economy approaches.