U.S. Political Dysfunction

In October of 2013, the U.S. government shut down for sixteen days. The government came within hours of risking default on the “risk-free” financial instrument (U.S. debt) that’s the foundation of the world’s financial system. These episodes followed the country’s partial dive off of the “fiscal cliff”, which resulted in the “sequester” – automatic, arbitrary budget cuts designed to be so painful that they would force Congress to come up with an alternative (Congress didn’t). The sequester mechanism itself was created after the government had previously come close to default in August 2011, sparking a more than twenty-two percent decline in the stock market and the first downgrade of U.S. government debt in history. Meanwhile, as the U.S. political system lurches from crisis to crisis, fundamental, long-standing problems go unaddressed, and the American public’s assessment of its political institutions, according to polls, drops lower and lower.

What is going on? Why are America’s political institutions producing these outcomes (or non-outcomes) and eliciting such anger and frustration from the American people? And, most importantly, what can be done about it?

Many commentators and political scientists place the blame squarely on America’s inexorably rising political polarization – what Princeton political scientist Nolan McCarty calls “the central challenge to good governance in the contemporary United States” and what Brookings and AEI political scientists Tom Mann and Norm Ornstein call “undeniably the central and most problematic feature of contemporary American politics.” And, in the growing conversation about what to do about it, a few of the preeminent scholars in this area have taken an insurgent position: that the best thing we could do to reduce political polarization would be to strengthen political parties rather than weaken them.

Rather than viewing the fundamental problem as the disappearance of moderates in the face of ever more polarized and powerful parties, these scholars view the fundamental problem as one of fragmented, weakened parties that have been disarmed to the point where they are beholden to their fringe elements. Or at least, in the weaker articulation, these scholars think it will not be possible to re-create depolarized parties with moderates and cross-cutting coalitions – and believe, therefore, that the only hope is to empower polarized party mainstreams against their even more polarized extremes.

However, this line of thinking seems to fly in the face of a lot of the newer and most innovative work on political parties. For example, work by the “UCLA School” (Bawn, Masket, Karol, and others) emphasizes the ways in which parties are not, as many conventional views hold, political entrepreneurs seeking to appeal to the median voter. Instead, parties are seen as coalitions of interests seeking to get away with as much as they can without the voters’ noticing. Rather than the Republican Party’s being prodded by the NRA, this view emphasizes the ways in which the Republican Party simply is the NRA – only constrained to the unlikely extent that something the party does breaks through the electorate’s general inattentiveness and starts costing it elections.

Which view is correct? With complex systems such as these, it’s hard to come to a definitive answer. And some of the evidence offered is unpersuasive. For example, in support of the idea that strengthened parties might help, Ray La Raja and Brian F. Schaffner have found that moderate incumbents in state legislatures receive more of their campaign finance from parties, while more extreme candidates raise higher proportions of their funds from other sources (individuals, issue groups, and business groups). This suggests that parties might help moderates more. However, they don’t have a good explanation for why that relationship only exists in states where parties can make unlimited contributions to candidates (in other states, the most extreme Republican candidates receive more of their financing from parties).

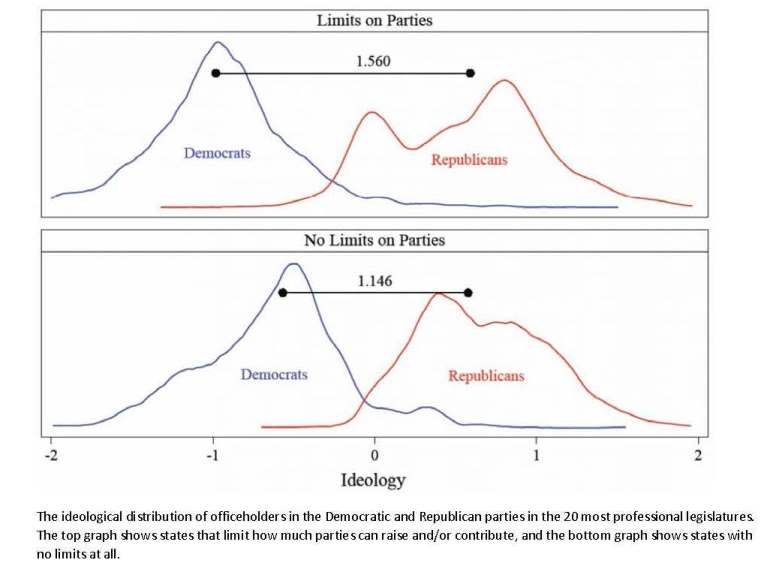

In a Washington Post blog, the authors also provide the following graph, which they interpret by saying, “In states where parties face more restrictive campaign finance laws, legislators are [more polarized] than in states where parties are financially unconstrained”:

However, the figure doesn’t necessarily show anything of the sort. It’s at least as likely to indicate only that more liberal states (or states with more liberal Democrats) tend to be the ones that adopt contribute limits. Moreover, if, as many scholars agree, political polarization has been primarily a function of the Republican Party’s moving further to the right, then this figure, which shows no effect at all on the Republican side, would seem to argue against the idea that weakening or strengthening of parties (at least by imposing or removing party contribution limits) have had anything to do with political polarization or might do anything to solve it.

For now, the debate is at an impasse. Part of my work at Yale has involved trying to find more empirical support for the party-strengthening hypothesis at the state level – but I have so far have been unsuccessful. It may turn out that the party-strengthening solution is as unsupported by evidence as several other potential solutions, such as nonpartisan redistricting or primaries, that are now viewed dismissively by many scholars.

Aaron Goldzimer’s research focuses on political polarization, gridlock, and democratic reform. He was an ISPS Graduate Policy Fellow (2014-2015) and graduated Yale Law School (2015). He was also the recipient of the David and Lucile Packard Foundation Fellowship at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business and the Dean’s Fellowship at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, where he was also a Spring Exercise winner and published in the Kennedy School Review