Candidates Can Be Rewarded for Speaking Spanish, but Evidence Suggests a Cost

[This article is reposted in its entirety from LSE US APP on September 23, 2019. ]

Candidates can be rewarded for speaking Spanish, but evidence suggests there might be a cost

In recent presidential elections, in order to attract a wider pool of potential voters, both Republican and Democratic primary candidates have often made appeals in Spanish as well as in English. But do these appeals have an electoral payoff for candidates? In new research, Alejandro Flores and Alexander Coppock find that bilinguals who saw Spanish language ads were more likely to vote for certain candidates than when they saw ads with the same contents in English. Voters who only spoke English, on the other hand, were turned off by seeing Spanish-language ads, especially from White candidates.

In recent presidential elections, in order to attract a wider pool of potential voters, both Republican and Democratic primary candidates have often made appeals in Spanish as well as in English. But do these appeals have an electoral payoff for candidates? In new research, Alejandro Flores and Alexander Coppock find that bilinguals who saw Spanish language ads were more likely to vote for certain candidates than when they saw ads with the same contents in English. Voters who only spoke English, on the other hand, were turned off by seeing Spanish-language ads, especially from White candidates.

During the first Democratic primary debate for the 2020 presidential election this past June, four candidates (Beto O’Rourke, Cory Booker, Julian Castro, Pete Buttigieg) chose to answer some questions in Spanish during the nationally televised event broadcasted on an English-language network. Spanish-language appeals have already emerged as a stand-out, opening narrative in the race for the 2020 presidential election. If, when, and where candidates decide to market themselves to Latino voters in this way now attracts a great deal of attention.

Not only are candidates for political office in the United States increasingly running multilingual campaigns, but this type of engagement no longer segments its audience based on language. Appeals in Spanish now form part of a candidate’s general mobilization strategy and the potential for exposure to this kind of messaging is greater than before. But it is not obvious how or whether these cross-linguistic appeals will pay off. In new research, we attempt to shed some light on this question by measuring the consequences of using Spanish-language versus English-language appeals in campaign advertisements.

Our study consists of a series of survey experiments conducted on large, diverse samples of both monolingual and bilingual Americans. We identified three candidates who produced otherwise identical versions of the same advertisement in both English and Spanish: Jeb Bush running in the 2016 Republican Presidential Primary, Democrat Filemon Vela running for Congress in Texas’s 34th district, and Republican Mike Coffman running for Congress in Colorado’s 6th District.

Many candidates produce both English and Spanish advertisements, but usually, when the language changes, so too does the content. But in our case, we found ads that had nearly identical context but differed only in the language of communication. We could therefore answer two questions well. First, does the Spanish-language ad increase candidate support over and above the English-language ad among bilinguals? Second, does the Spanish-language ad have unintended consequences if it is “mistargeted” to English-only monolinguals?

What’s it worth?

Our analysis shows that among bilinguals, these campaign efforts in Spanish do have a positive effect on support for a candidate; a markedly different and greater electoral returns than did the same venture in English. Figure 1 shows our main results.

Figure 1 – Support for candidates among bilingual subjects

Bilingual subjects who saw Jeb Bush tout his legislative record in Spanish were 4.9 percentage points more likely to vote for him in the general election than bilinguals who saw the English-language version. This difference in effect cannot be explained by the substance contained in the ad since Bush went over the same talking points and script in both versions. We speculate that Bush’s Spanish-language appeals were seen as particularly authentic, perhaps because it is well-known that Bush is married to a woman of Mexican heritage or simply because he is a proficient Spanish speaker.

“Romain Gérard : Speech balloons” by Marc Wathieu is licensed under CC BY NC 2.0

In a follow-up experiment, we explored the possibility that the effects are contingent on the identity of the speaker. Filemon Vela’s own appeal in Spanish, for example, did improve levels of electoral support for him by 4.9 percentage points (identical to point estimates for Bush). Yet, this effect does not appear to extend to Mike Coffman, the Republican congressional candidate, who received no electoral gains from bilinguals who saw his Spanish-language ad—a meager 0.3 percentage point difference. We can only speculate as to the reasons why. The explanation cannot lie in his being White or being Republican only, as Jeb Bush shares both those characteristics and the Spanish-language ad worked well for him.

At what cost?

Even though the use of Spanish tends to have positive effects among bilinguals (at least for some candidates), pursuing a multilingual campaign strategy for a wider audience that includes both bilinguals and monolinguals is nevertheless a gamble.

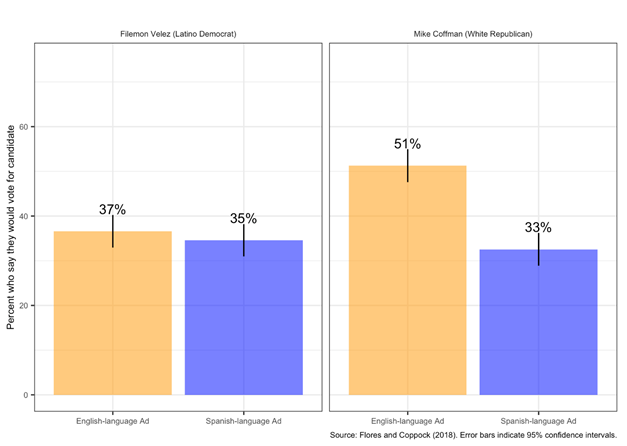

Our analysis shows that the language of communication does influence vote choice even if a message is in a language they do not speak. Among English-only monolinguals, seeing a candidate speak Spanish can lead to a decrease in support. For Vela, this negative effect was relatively mild, at -2 percentage points. But for Coffman, the effect was devastating, at -19 percentage points. Figures 2 illustrates the dramatic extent of this negative reaction.

Figure 2 – Support for candidates among monolingual subjects

In our work, we explore the possibility that different kinds of monolinguals respond to the ads differently. We investigate whether the large negative average effect we see among monolinguals to the Spanish-language appeal is especially large among Democrats or Republicans. In short, we do not find evidence of such heterogeneity. Both Republican and Democratic monolingual respondents react very negatively to the Spanish-language appeal, and by similar amounts.

The future of Bilingual Messaging

Clearly, if candidates face electorates that are composed of monolingual English speakers, monolingual Spanish speakers, and bilingual English and Spanish speakers, they would ideally like to create language-specific appeals to each of the monolingual groups. In practice, such as in the recent Democratic debate, candidates have begun to seize any opportunity to communicate their linguistic familiarity, leaving aside clear differences in comprehension of its viewers. For candidates in our study, such an oversight can have important consequences.

Candidates who are considering producing Spanish-language advertisements must weigh the benefits of directly appealing to Spanish-speakers against the potential costs of reaching exclusively English-speaking constituents. Our results shed light on the strategic calculus of candidates who must appeal to multiple linguistic communities at once. For the 20 Democrats running for president, for example, our study can help calibrate the apparent tradeoff that they will face when considering a media plan that includes the use of Spanish.

Suppose for the moment that the positive effect among bilinguals is 5 percentage points but the effect among English-only monolinguals is negative 15 percentage points. If the electorate is only composed of those groups, then the payoff to a multilingual campaign will depend on two parameters: the proportion of bilinguals in the electorate and the mistargeting risk, which we parameterize as the probability that a monolingual encounters the Spanish language ad. When the electorate is 0 percent or 100 percent bilingual, the respective strategies are clear: use English or Spanish exclusively. When bilinguals are a proportion of the electorate, the use of targeted ads is advisable, so long as the risk of mistargeting is not too great. But because of the extreme downside risk of mistargeting relative to the possible benefit of correctly targeting bilingual constituents, candidates should be cautious when pursuing a Spanish-language advertising strategy, even when more than 50 percent of the constituency is bilingual.

That said, the electoral pros and cons of choosing to communicate in Spanish should not be the only inputs into candidates’ decision making about this issue. Promoting an inclusive politics that brings together Americans from multiple linguistic communities may be an important end in and of itself that is worth pursuing regardless of the consequences of “mistargeting.”

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Do Bilinguals Respond More Favorably to Candidate Advertisements in English or in Spanish?’ in Political Communication

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2m1CAyM

About the authors

Alejandro Flores – University of Chicago

Alejandro Flores is a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of Political Science, University of Chicago. His research agenda focuses on experiments in the study of political persuasion and attitude change, race, and identity

Alexander Coppock – Yale University

Alexander Coppock is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Yale University and ISPS Faculty Fellow. He studies how individuals incorporate new political information and the reproducibility of social science research.