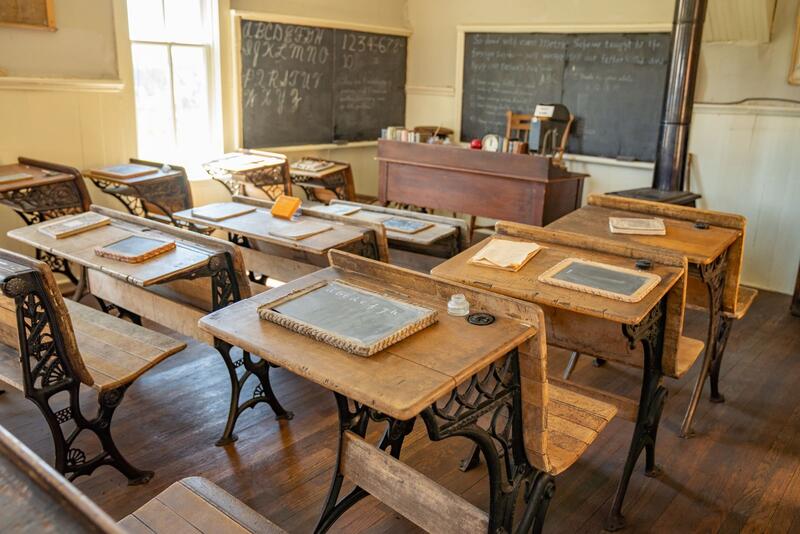

Did Publicly Funded Education Promote Democracy in Early America?

The January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol sparked an ongoing debate about how widely held democratic values are in the United States and what can be done to strengthen those values. One commonly proposed prescription is revitalizing public education about the duties, as well as rights, of citizenship in democratic societies. It is a familiar theme in American history with some of the earliest efforts to publicly fund education in the 19th century having civic education as a leading rationale.

The January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol sparked an ongoing debate about how widely held democratic values are in the United States and what can be done to strengthen those values. One commonly proposed prescription is revitalizing public education about the duties, as well as rights, of citizenship in democratic societies. It is a familiar theme in American history with some of the earliest efforts to publicly fund education in the 19th century having civic education as a leading rationale.

In a paper published this month in the American Political Science Review, Kenneth Scheve, Dean Acheson Professor of Political Science and Global Affairs and Faculty of Arts and Sciences dean of social science, and his co-authors examine whether these efforts in the early republic worked. Did state funding of education nurture a culture of participatory democracy?

Scheve, a faculty fellow with the Institution for Social and Policy Research (ISPS); Tine Paulsen, assistant professor of political science and international relations at the University of Southern California; and David Stasavage, Silver Professor of Politics at New York University, utilized a natural experiment in which some towns in Central New York were provided additional financial support for education based on funds established when the area was first being settled.

Analyzing outcomes from the mid-1800s by comparing neighboring regions that differed in access to a geographically determined external source of education funding, the authors found that greater public funding of primary school education led to improved earnings, lower inequality, and higher voter turnout. The authors argue that the historical circumstances that led to sharp differences in public education funding in these towns allow for the differences to be interpreted as the causal effect of greater education spending.

“We interpret this result as suggesting that, in this case, we have an example where even if initial endowments were favorable to democracy, creating a participatory democratic culture depended on subsequent political choices, and perhaps the most important of these was to educate the population,” they wrote.

Examining gubernatorial elections in 1842 and 1844 and the presidential election in 1844, the researchers found that residing within the towns receiving additional public education funding contributed to a 3-percentage point increase in eligible voters casting ballots. This was true even as those elections were very competitive and overall turnout was high.

“Our findings support the view that maintaining democracy requires active investments by the state,” the authors wrote. “Something that has important implications for other places and other times — including today.”