Partisan Gerrymandering Mostly Cancels Out at National Level, Study Shows

In many states, political actors draw district lines for choosing federal congressional representatives — one winner for each district. Often, they draw lines to the advantage of their own party and to protect their incumbents, a practice known as partisan gerrymandering.

But because of how Americans naturally sort themselves geographically or are systemically segregated by partisan affiliation and race, political scientists have questioned the size of the effect gerrymandering alone has on the composition of Congress. How much of the electoral bias seen at the national level can be traced back to these party-led efforts?

In a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Yale’s Institution for Social and Policy Research (ISPS) faculty fellow Shiro Kuriwaki and his colleagues at Harvard University provide an answer to that question. They analyzed simulations to compare the current district mapping plans enacted after the 2020 census to alternative, nonpartisan plans that satisfy the same constraints set by courts and state legislatures.

Simulations are increasingly used as evidence to evaluate partisan gerrymandering cases in court. Kuriwaki is part of a team that has created simulations for all U.S. states and released the data and algorithms of those simulations for the public.

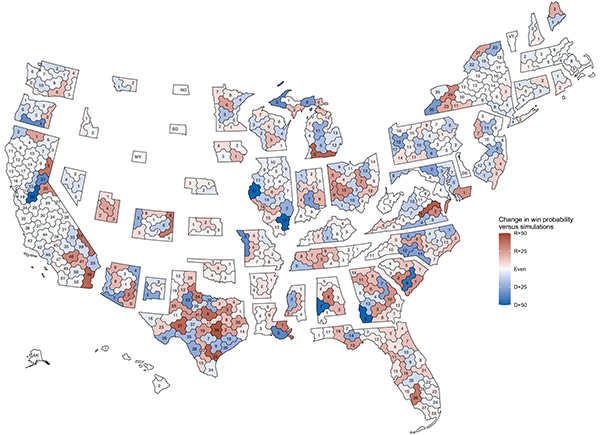

They found widespread partisan bias in the current, enacted plans. For example, Republican efforts to engineer maps to their advantage by packing Democrats into urban districts appear to have been successful in states such as Texas, Florida, and Ohio. Democrats achieved smaller advantages, especially in Illinois. And plans drawn by courts and commissions in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Michigan ended up slightly more advantageous to Democrats relative to simulated plans.

Taken together, the data shows that most of the electoral bias cancels out at the national level, resulting in only a two-seat advantage for Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives compared to what could have been drawn under geographic and legal constraints.

“However, this does not mean that the partisan gerrymandering — and the political contestation over redistricting — was inconsequential,” the authors wrote, noting that they found Democrats are structurally and geographically disadvantaged by eight House seats. “Many states have enacted districting plans with partisan biases that decrease electoral competitiveness and responsiveness, limiting the voter’s ability to hold politicians accountable.”

Kuriwaki and his co-authors — Christopher T. Kenny, Cory McCartan, Tyler Simko, and Kosuke Imai — found that for Democrats to win a majority of the districts to control the U.S. House of Representatives under the new 2022 congressional district map, they need to amass more than 51.1 % of the national popular vote. But this is only .14 percentage points more than the popular vote Democrats would need if every state were to draw nonpartisan maps under the current geographic and legal constraints.

“These findings illuminate the inherent difficulty of producing a fair national House map when it is drawn piecemeal by 50 autonomous political units,” the authors wrote. “More research is needed to further advance our understanding of the crucial relationship between votes and seats that structures American democracy.”

Kuriwaki said that simulations alone cannot detect the intent behind gerrymandered plans conclusively. For example, he noted a recent decision from a new Republican majority on the North Carolina Supreme Court that reversed the court’s previous Democratic majority opinion deeming partisan gerrymandering to be illegal and cleared the way for Republicans in power to shape the districts to their advantage.

“In this article, we effectively defined gerrymanders as outlier plans drawn by partisan state legislatures,” he said. “But the ruling by the new justices of the North Carolina Supreme Court that came out since writing this article highlights how formally nonpartisan institutions could enact partisan intent.”

Kuriwaki teaches classes on Congressional policymaking and quantitative research design while helping ISPS launch Democratic Innovations, a program designed to identify and test new ideas for improving the quality of democratic representation and governance. His recent research addresses winning elections with unpopular policies in Japan and the geography of racial voting in the United States.