Yale Hosts International Bioethics Summer Program

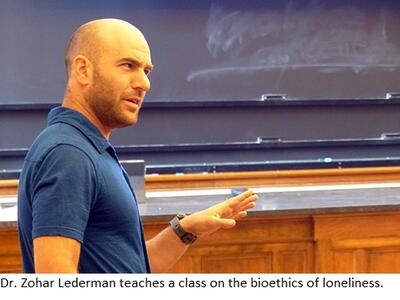

In a well-populated classroom, Dr. Zohar Lederman led a lively and empathetic discussion on the bioethics of loneliness.

“We often don’t ask about loneliness in our patients,” Lederman said. “And when we do, we don’t do anything because it’s outside our paradigm.”

But Lederman, a public health ethicist and emergency department physician living in Hong Kong, aims to change that perception. He notes that people who suffer from loneliness die faster, with higher blood pressure, weaker immune systems, and other health problems. Because physicians so often focus on acute medical issues, they can unintentionally neglect clear symptoms of loneliness, which disproportionately affects people who are elderly, people with disabilities, and teenagers, he said.

“If we agree that public health should be about mental health in general and include loneliness to some degree, we have an obligation as part of the community to help people not to be lonely,” he said. “What is the way to do that?”

These and many similar questions filled the seven-week Sherwin B. Nuland Summer Institute in Bioethics, run by Yale’s Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics, which is supported by the Institution for Social and Policy Studies.

“ISPS is tremendously proud to support the Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics,” said ISPS Director Alan Gerber. “The summer program has justifiably grown into an exemplary destination at the very forefront of scholarship and international collaboration to explore moral considerations within the most urgent, constantly evolving topics we face as a society.”

Begun in 2006 as a program for Yale College students, the summer institute now invites people from around the world, across different fields, and at various career levels. Before and after the pandemic, about 70 students attend in-person seminars on contemporary pressing issues in bioethics, with another 75 attending an online introductory course on the foundations of ethical theory, ethical policymaking, and bioethical principles, terms, and history.

“We are increasingly facing complex and time-sensitive ethical challenges ,” said Lori Bruce, associate director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics and director of the summer program. “Vulnerable communities are becoming even more fragile due to global warming, war, and the changing nature of reproductive rights in many states.”

The program aims to provide attendees with tools and resources to explore principles of bioethics across disciplines, in an affordable and hands-on way. And then to return home and help raise awareness among colleagues and classmates.

“We include clinicians, legal scholars, social workers, and philosophers,” she said. “It’s not uncommon for a physician from Turkey to engage in a morally laden discussion with a legal scholar from Singapore and a divinity student from Nepal.”

This year’s class represents students from more than 20 countries, including Afghanistan, Singapore, India, and Brazil.

“As someone with an international background and a global orientation, I am really happy that everyone in this seminar is from different places,” said Nathifa Greene, an assistant professor of philosophy who teaches bioethics at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania.

She attended this year’s program to gain the insight of clinicians and people who work in policy and various disciplines so she can revamp and reframe her course materials in consideration of new technologies and the changing legal landscape represented by developments such as the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision eliminating the constitutional right to abortion.

“So, we are learning about health care systems in different places — different kinds of cultural questions in bioethics,” Greene said.

In addition, attendees’ professional development ranges from established educators like Greene to undergraduate students like Abigail Murphy, a Canadian citizen who is studying philosophy at the University of Guelph in Ontario with the goal of becoming a clinical bioethicist and educator focused on disability advocacy.

“The people who I am meeting and the experiences that are being shared with me from such a global perspective are things that I would never have been able to come to see or understand,” Murphy said. “I can tell how much this is going to help me moving forward. It’s already helped me so much just in my general understanding of the field.”

Stephen Latham, director of the Interdisciplinary Center for Bioethics, said several past attendees have gone on to earn doctoral degrees and then return to teach.

“We want to make the summer program the best place in the world to get a beginner’s introduction to bioethics,” Latham said.

Bruce said she extends the program’s mission to “nudge bioethics to become more inclusive and collaborative — but also more methodical and influential.” In her ethical policymaking seminar, she fills a gap in bioethical frameworks that are otherwise limited to clinical and research settings.

Elena Brodeala, a faculty member at Paris Institute of Political Studies and alumna of Yale Law School, attended this year’s summer program. She said Bruce’s seminar meets a profound need by teaching how to communicate ethical complexities to policymakers, including how to infuse legislative testimony with moral arguments and how to work together despite differences to meet the needs of the communities they serve.

“The global challenges we face today require bioethicists to extend our core set of skills to include writing op-eds, giving testimony, and writing policy briefs,” Brodeala said. “The policy seminar gave us that knowledge but also highlighted the value of having different perspectives at the table and how collaborating with international colleagues from very different backgrounds enriches design within policymaking. This is key for the local and global levels to ensure that those who are most affected by transnational challenges such as pandemics and climate change have their interests represented.”

Bessie O’Dell attended the program in 2019 and is now in a doctoral program in psychiatry at the University of Oxford.

“The program was amazing for me,” O’Dell said. “It has really shaped the last few years of what I’ve done in terms of my research. I had no real introduction to bioethics before. It really gave me some grounding principles — a really broad understanding of the areas of bioethics you could get involved in.”

She now recommends the program to others, even those with no background in ethics, medicine, or philosophy.

“I think even if you don’t know that ethics will come into your work or research, it’s so helpful to think about these perspectives,” O’Dell said. “So even if you are doing English literature or something completely random, that’s fine. Have a look at the program, and if it interests you, apply.”

This year’s program ended with a poster presentation at The Anlyan Center, where students discussed their projects on questions such as: When is paternalism morally justifiable? What are the ethical and practical limitations of letting patients propose amendments to their electronic health records? What are the ethical implications of hospital mergers? Is there a way to resolve the moral tension when deaf parents using pre-implantation genetic diagnosis for in vitro fertilization select for the presence of deafness in a child? And what ethical dilemmas are created when using artificial intelligence for medical decision-making?

“I think that so much of bioethics or ethics in general seems to be so cerebral and just kind of discussions on a theoretical basis,” said Aliza Goldman, a former nurse working on a Ph.D. in bioethics at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. “And when you come to a program like this, you realize what you can do with this kind of knowledge and bring it out to the real world.”

For Dr. Evie Marcolini, who practices emergency medicine and neurocritical care at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire, teaching at Yale’s summer program is a form of advocacy. She wants to share with up-and-coming physicians, lawyers, and social workers that they have a role to play when confronting inevitable ethical issues in their work.

“To bring the message out there that it’s not just my job to diagnose myocardial infarction or to diagnose diabetic ketoacidosis,” Marcolini said. “The more we continue making bioethics an important topic in everything we do, the closer we get to actually raising awareness and changing things from the ground up.”

Mary Lou Gaeta, a pediatrician at Yale New Haven Children’s Hospital, attended the program for the opportunity to discuss questions that have been irking her for years. Even if she understands there are no easy answers.

“It’s important to recognize that these issues are there and to call them what they are,” Gaeta said, noting that decisions are being made that affect patients even if the decision-makers aren’t considering the ethical implications.

Gaeta praised the program for providing an invaluable opportunity to exchange ideas with people of different backgrounds, experiences, and viewpoints.

“There isn’t often a space to focus in on these issues around us and look at them through a lens that would influence our practice,” she said. “And hopefully make it better for the patients that we treat, the people that we live with, and society in general.”