Cutting the Gerrymandering Cake: “Define-Combine Procedure” Reduces Partisan Bias in District Maps

Political scientists don’t normally look to the bible for solutions to intractable problems. But maybe difficult times call for a modern application of ancient wisdom.

A story in Genesis describes how Abraham divided the land of Canaan into northern and southern parts and gave Lot his choice on which to settle and tend to his herd. This form of “fair-cake-cutting” has evolved into a handy method for parents to manage disputes among children and a thriving field of theoretical mathematics involving complicated procedures to ensure proportionality.

But no one has fully applied such a method to the real-world conundrum of how to create fair legislative districts. Until now.

Kevin DeLuca, faculty fellow with the Institution for Social and Policy Studies and assistant professor of political science, collaborated with Maxwell Palmer of Boston University and Benjamin Schneer of Harvard Kennedy School to devise a new method for drawing districts that, in their words, “reduces partisan gerrymandering without requiring a neutral third party (such as an independent commission, judge, or tiebreaker) or bipartisan agreement.”

“We took some inspiration from the cutting-the-cake problem and theoretical mathematical models that abstract away from geographic constraints, make assumptions about the distribution of voters, or require multiple rounds of complicated bargaining,” DeLuca said. “But we wanted to think concretely about how to devise a way in which states could apply this technique in a practical way using data from the real world.”

In a paper published in the journal Political Analysis in December, the researchers reveal the Define-Combine Procedure (DCP), in which one political party chooses contiguous, equal-population districts and the opposing party combines pairs of these selected districts to create the final districts. For example, if a state required 10 districts, the state’s Democratic representatives might define 20 districts, and then the Republicans would choose which neighboring pairs to combine and form a 10-district map.

Palmer created a website that includes the ability for users to run simulations and observe how DCP works.

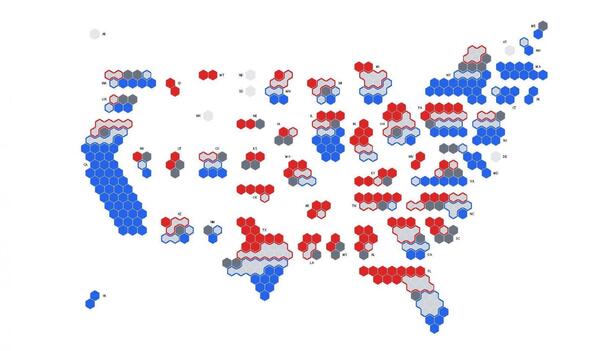

The map above shows results of simulations in which congressional districts colored blue are always won by Democrats and those colored red are always won by Republicans, regardless of which party controls the process — either through DCP or a method in which the majority party controls the process unilaterally. Districts shaded in light or dark gray could be won by either party if given unilateral control. Dark gray districts could be won by either party if utilizing DCP. And those outlined in blue would be won by Democrats using DCP, with those outlined in red won by Republicans using DCP.

“This process allows each party to act in their own partisan self-interest but achieves a significantly fairer map than would be drawn by either party on its own,” the researchers write in a summary of their paper. “By dividing the responsibility into two separate steps, in which each party retains complete control, the parties counteract each other’s partisan ambitions while maintaining considerable flexibility to achieve other objectives, including maintaining compactness and communities of interest.”

DCP works by reducing each party’s ability to pack districts of the opposing party’s supporters into as few districts as possible — reducing their representation in Congress — or to split up communities into separate districts and combine districts that are distant from one another. This makes it much harder to draw districts that unfairly increase or maintain a party’s legislative majority.

The researchers ran thousands of simulations using 2020 election results from every state, comparing redistricting outcomes either applying DCP or if the parties had unilateral control to draw the maps. They found that DCP substantially reduced partisan advantage.

For example, if Republicans in Texas held complete control of creating the state’s legislative districts, they could draw a map with 30 Republican seats in Congress and only eight Democratic seats — a 22-seat advantage. Similarly, Democrats in charge of the process could give their party an 18-seat advantage. But the simulation applying DCP created 19 Republican seats and 17 Democratic seats, regardless of which party defined the districts and which party combined them in the second phase of the process. In these scenarios, the defining party would gain the remaining two seats.

Alan Gerber, ISPS director and Sterling Professor of Political Science, praised the paper for advancing the aims of the Democratic Innovations program to identify and test new ideas for improving the quality of democratic representation and governance.

“DeLuca and his co-authors do something ingenious, taking what might seem like a simple concept and seeing how this idea can be applied to a complex problem in political representation,” Gerber said. “In doing so, they have expanded the policy options available to those who want to rethink how we draw our legislative districts.”

DeLuca said a party with control of the process would be unlikely to give up their power to gerrymander districts in favor of the fair-cake-cutting DCP approach. But he said that states in which courts or commissions have assumed map-making responsibilities, DCP provides a promising option or at least a guidepost toward a fair outcome.

“Sometimes independent commissions have failed to pass a map because negotiations broke down or there is an evenly divided board,” DeLuca said. “Courts might not want to draw maps themselves and potentially be seen as partisan.”

In these cases, a commission acting in good faith can adopt DCP to draw the map or create a benchmark for fairness before continuing its work, he said. Or a court could order the use of DCP when a commission or legislature fails to pass a fair map, allowing legislators to maintain their ability to define district boundaries while avoiding gerrymandering’s harms to democratic accountability and electoral competition.

“Our method gives the court a way out and a structure to ensure a fair outcome,” DeLuca said. “And it does it in a way where we know, empirically, that the resulting map will be less biased and more representative.”