The Politics of the Multiracial Right

On a street corner above a storefront window on the South Side of Chicago, a dark blue awning advertises the presence of the Southside Republicans’ Booker T. Washington & Ida B. Wells Renaissance Center. In the left corner it reads: “FIX WHERE WE LIVE.” A post on X announcing the center’s opening in March included the hashtag “turnchicagored.”

Based on party affiliation and history, a majority of voters in Chicago will almost certainly not vote Republican in November’s elections. But polls across the country have shown increasing support for Donald Trump among Black and Latino voters, including those in urban centers. Conservative groups, even those espousing white supremacy, have attracted growing numbers of people of color.

These trends are emerging even as Republican officials and candidates unapologetically deploy or tolerate racist tropes and take hardline stances on racialized policy issues, such as affirmative action, voting rights, immigration, public safety, housing, and reproductive justice.

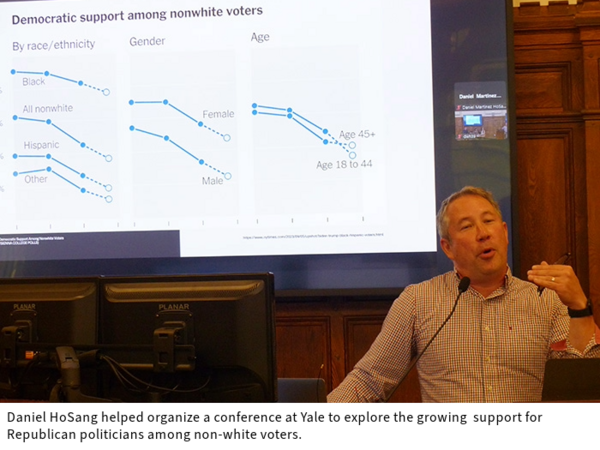

On Friday, Yale hosted interdisciplinary scholars, journalists, and political analysts for a symposium to help interpret these developments and what they might mean for the future of politics and social movements in the United States and the world. The event was sponsored by the Institution for Social and Policy Studies (ISPS) and the Yale Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration (RITM).

“After Trump was elected in 2016, the idea that four years later, 40% of Latinos would say, ‘That’s my guy’ seemed farfetched — and that’s exactly what happened,” said Daniel HoSang, a professor of American Studies affiliated with ISPS who helped organize the symposium and has written extensively on race and conservative politics. “Very few people who do this work would have anticipated that or can even explain or theorize it.”

HoSang and his co-organizers, Joe Lowndes, a lecturer in American politics at Hunter College; and Micah English and Minali Aggarwal, Ph.D. students in political science affiliated with ISPS’s Center for the Study of American Politics, will continue to build out the Politics of the Multiracial Right project. A volume of essays, co-edited by HoSang and Lowndes with original pieces by English and Aggarwal, will be published by New York University Press next fall.

English said that the project overturned their assumptions that this was a niche phenomenon mostly involving men of color.

“We’ve come to realize that what we are seeing is a lot more complicated and a lot more dynamic than what can be captured by simply looking at polling numbers or paying attention to national politics,” English said. “The political right is making inroads with many communities in ways that are surprising and challenging to many conventional assumptions about race and gender and where and how political identities are formed.”

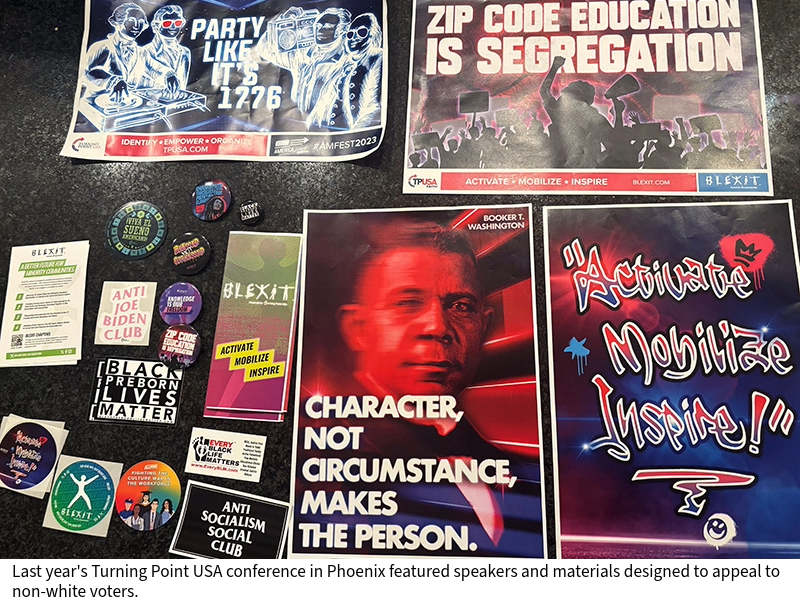

Their research included consuming right-wing media and attending events, such as last year’s Turning Point USA conference in Phoenix aimed at students and young adults. HoSang described two young Latino political strategists electrifying the mostly white crowd with messages about how to appeal to people like them, who they said are ready for something new.

“They were saying we can bring these folks over not by watering down the message,” HoSang said. “We can bring the full weight of the MAGA message to them. They had this MAGA white crowd giggling in delight. And I thought, how did it come to be that these two men became so deeply invested in this?”

In an event the previous day, HoSang and English hosted a conversation with the conservative journalist, pundit, and communications consultant Sonnie Johnson about understanding the growth in Black conservativism.

Raised in Richmond, Virginia, Johnson has described how her blog, initially non-political, began attracting attention from Republicans who encouraged her to voice her observations, contrasted sharply with the backlash she received from Democrats, who labeled her a sellout. HoSang quoted her insights into why the Republican Party might appeal to young people of color.

“On conservatism and insurgency, the young generation always likes to be the rebels,” she said. “It puts us in a strategic position because the left is now the system. The left is now The Man. The left is now the structure. It’s only natural for me to want to rebel against that, and that rebellion will bring them into conservatism.”

In addition, the conference featured a panel on gender, culture, and the multiracial right. Christina Beltrán, an associate professor in New York University’s Department of Social and Cultural Analysis, discussed the role of Latina Republicans like Susana Martinez, the former governor of New Mexico.

Beltrán noted how Martinez leveraged her identity to appeal to voters, using a mix of maternal protection rhetoric and xenophobic characterizations of migrant men.

“She created an affective chain, linking sexual predators, endangered children, and undocumented immigrants,” Beltrán said illustrating the powerful and sometimes controversial strategies employed by conservative women of color. “Liberals often think, well, the only way Republicans are going to attract more people of color is by approaching issues in a more moderate way. I actually think that because of these kinds of assemblages, it makes it possible for right-wing women of color to be able to say even more radical things.”

Priscilla Yamin, professor and chair of women and gender studies at Hunter College, examined the conservative women’s beauty magazine, Evie. Yamin highlighted how the magazine, founded in 2019, filters femininity and empowerment through a conservative lens.

“Evie’s content is designed for young women by young women, and it offers novel ways to support a conservative agenda of anti-abortion, anti-trans, and anti-feminism, while at the same time supporting women in their work, education, and goals,” Yamin said. “Evie’s conservatism is not seemingly grounded in this harmonious, mythic past of the traditional nuclear family, racial purity, and whiteness. Rather, they draw from the histories of racial and gender struggle and exploitation to anchor and legitimize their politics of anti-corporatism, anti-government, and anti-liberal agenda.”

English and Loren Kajikawa, chair of the music program at George Washington University’s Corcoran School of the Arts & Design, discussed their research on the intersection of hip-hop culture and conservative politics. They cited examples of rappers such as Kanye West and Lil Wayne endorsing Trump, as well as the emergence of right-wing rappers who use hip-hop to advance conservative agendas.

“We think about the GOP being out of touch with hip-hop and having no interest in hip-hop, when in fact, there are conservative operatives paying attention to what’s going on in hip-hop, mining it for content, and trying to figure out how hip-hop can advance their cause,” Kajikawa said. “Hip-hop is being deployed in a way that advances right-wing intersectional politics. They’re very aware of where the fissures are in hip hop culture — around sexuality and gender, for example — and are using hip-hop to appeal to men of color and others who uphold traditional ideas about masculinity and patriarchy.”

Throughout the conference, speakers emphasized the need for a nuanced understanding of the political right’s diversity.

“What we hope to accomplish with this symposium and with the volume is to demonstrate that the right is not one single thing,” Aggarwal said. “You don’t need to hold a coherent ideology or believe in a singular set of policies to identify with the right. And you certainly don’t need to be ashamed about your racial or your cultural identity.”