The Adaptability Paradox: Stephen Skowronek Explores How American Democracy May Have Outgrown the Constitution

The United States has changed dramatically over the 236 years since the Constitution’s ratification, and the Constitution has adapted to accommodate those changes. But what if the country’s growing democratization has outpaced the Constitution’s ability to adjust?

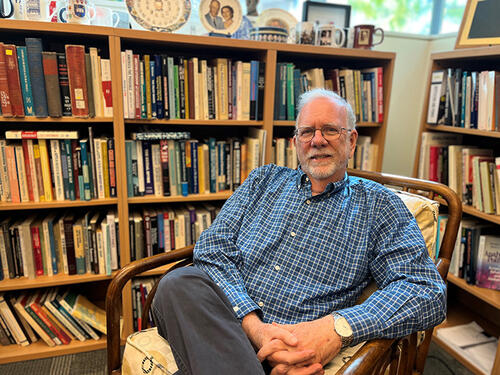

Stephen Skowronek, Pelatiah Perit Professor of Political Science and Professor and faculty fellow with the Institution for Social and Policy Studies, has a new book, “The Adaptability Paradox,” in which he explores this question.

In this conversation, edited for length and clarity, we explore his argument that expanding political inclusion through structural innovations and advancements through the Civil Rights Movement may have hollowed out the Constitution’s integrity, leaving it unable to support further democratic development and manage conflict in a large, pluralistic society.

ISPS: Why did you write this book?

Stephen Skowronek: These are tough times for constitutional government in the United States. In some ways, we fit a general pattern of democratic backsliding. So, what’s my value added in this conversation? Rather than compare the U.S. to what’s going on elsewhere in the world today, my set of comparisons looks to the history of our constitutional development and to how the American Constitution adapted to democracy’s advance in earlier periods. Democratization produced constitutional crises before. How did we adjust? How did we adapt? More importantly, is there anything about this moment that makes adaptation to democracy’s advance categorically more difficult?

ISPS: Everything’s history, right? It never repeats itself exactly.

Skowronek: Right. Sometimes it rhymes. Sometimes the differences overtake the similarities.

ISPS: Let’s get to your title — “The Adaptability Paradox.” How would you describe what that means to someone you might meet on the street?

Skowronek: Popular sovereignty is the Constitution’s most radical and democratic principle. Constitutional adjustments to democracy have periodically reconstructed constitutional government in the U.S. The paradox is that once “we the people” became a truly encompassing reality — once American democracy became fully inclusive — the Constitution’s capacity to reestablish firm footing and stabilize the polity began to dissipate. Paradoxically, serial adaptations to democracy have loosened up the old structure to the point where it no longer seems capable of holding the democracy together.

ISPS: You suggest that through democratization the Constitution has become “unbound.” That the earlier exclusion of certain people from the full rights of citizens — most notably enslaved people, Indigenous peoples, women, and laborers — served to stabilize the system for the other groups who were being included. Why was that a good thing?

Skowronek: It certainly wasn’t good in a moral sense. Those exclusions were unjust and deeply damaging. But they were functionally stabilizing. And they were compatible with the Constitution’s complex structure. They allowed the Constitution to operate and adapt without collapsing under the weight of irreconcilable demands. Exclusions gave the system its ballast. Inclusion purged the ballast while, at the same time, loosening up the Constitution’s structural constraints.

ISPS: How so?

Skowronek: We celebrate the Constitution’s resilience, but historically, the resilience of the Constitution was socially bounded. By “bounded resilience,” I mean that the Constitution could adapt as long as some social issues remained beyond the reach of national power. There was always some social content that was fixed in hierarchical relationships and out of bounds. Race relations, labor relations, and family and gender relations were left to the states. And people in the subordinate positions were subject to rules that were not only different but quite incongruous with the rules that governed full participants. In serial waves of democratization, social movements overturned those hierarchical relationships, displaced those incongruous rules, and nationalized rights.

ISPS: Most recently and primarily the Civil Rights Movement, right?

Skowronek: Yes. As long as other systems of authority kept some conflicts under wraps, the Constitution could resolve the problems that came with accommodating others. The Rights Revolution of the 50s and 60s swept away the last of those alternative legal systems and brought all social conflicts into play. Suddenly nothing was beyond the reach of national authority, and no boundaries were secure. The Constitution had been designed for the protection and security of the interests who participated fully in the national government. But with full inclusion, the Constitution was unbound and no one felt secure. This unbound Constitution does not instill a sense of security. It universalizes anxiety.

ISPS: I see. In your telling, “bounded resilience” is a basically a dispassionate description of power dynamics.

Skowronek: Dynamics of development, yes. The book does takes an arm’s length view of this history. I don’t want anyone to think I’m blaming democracy or lamenting the overthrow of those old ways of governing. My point is that the relief offered by adaptation in the past was built on the backs of people who remained excluded. This is a big country with a lot of competing interests. People see the fundamentals very differently. It’s kind of fantastic that we were able to hold it together for as long as we did. But for a long time filtering out certain conflicts proved functional in resolving others.

ISPS: Can a fully inclusive democracy ever be structurally stable?

Skowronek: That’s the big question, isn’t it? What explains how we were able to adapt before and why we are having such a hard time now? Once you run out of exclusions, you get this circumstance where constitutional government starts spinning more wildly. Parties polarize. Courts get politicized. Rules and norms are no longer reliable. The Constitution doesn’t seem to be able to regain firm footing. Which raises your question: Is it possible to have a strong constitution that serves a fully inclusive democracy? That, it seems to me, is the goal. The book poses this question, but it does not answer it. It is not a happy book because I don’t see an easy way out of the current predicament. But I’m not willing to go the extra step and say that constitutional government requires exclusions. I do think the adaptability paradox has us caught in its grip, and it may be that this Constitution requires exclusions. But if that turns out to be case, we will need a new Constitution.

ISPS: You use the word “stability.” Was the country really stable, or was the stability more a feature of systemic racism and patriarchy?

Skowronek: It was stable to the extent that the Constitution managed conflict and kept the country together. Adaptations restored predictability and a sense of security. The lines of contestation became manageable again. Participants accepted and respected the rules of the game. And for a long time, new rules could be generated to accommodate new participants. The people who participated recognized that these were new arrangements, but they accepted them as arrangements consistent with what they expected from the Constitution. I’m describing how it worked — not saying that it was great. What I’m saying is that adaptation used to resolve crises and reset the system. Now our institutional innovations are not ameliorating our conflicts. They are magnifying our conflicts and digging us deeper into a hole. I’m asking, “What happened to our old knack for reinvention?” Is there a limit to our adaptations to democracy?

ISPS: You describe judicial supremacy — the principle that the Supreme Court has the final say on how to interpret the Constitution — as both a solution and a problem. What role should courts play?

Skowronek: Judicial supremacy is a formal solution — one internal to the structure of the Constitution. Previously, we did not rely on the Supreme Court to resolve problems of democratization and settle on new arrangements for our constitutional democracy. Historically, these were political settlements. Now we do depend on courts, and it turns out that courts are a poor substitute for a political settlement. Irreconcilable partisans scrambling over the appointment of judges who will wield “final authority” is symptomatic, because claims to final authority are no more compelling than the consensus behind them. Ironically, judicial supremacy rose to prominence under the democratizing left — the Warren Court. That idea was then seized upon by the right: “If they can do that, so can we — just get the right judges.” Both sides reflect a failure to generate political consensus under full inclusion. Both sides just muscled their preferences through.

ISPS: You also talk about the hollowing out of political parties.

Skowronek: Parties lost control over nominations in the aftermath of the rights revolution. The use of primaries expanded, and party managers were stripped of their control over the party organization. Conventions used to be management devices dominated by party “bosses.” Now they’re just showcases for candidates. In the Democratic Party, the Civil Rights Movement broke the hold of local party managers. There too the expansion of rights loosened old structures. Once Black people and women gained a voice, the party became a vehicle for what we call “intense policy demanders.” Candidates no longer served the party; the party served the candidates. That was more democratic, but the old function of managing social conflict fell by the wayside. And no new forms of management were forthcoming.

ISPS: And the Republican Party?

Skowronek: It became a radicalized insurgency aimed at dismantling the newly unbound, progressive Constitution. Neither party reconciles interests or manages conflict anymore — they articulate and deepen conflict.

ISPS: You suggested the administrative state once helped manage conflict. Why has it lost that capacity?

Skowronek: Coincident with the hollowing out of parties, public administration came under attack from both left and right. The left saw over-administration — “We’ve got to give power to the people.” The right saw bureaucratic overreach. Legislation began to bypass administration and direct people to the courts. Both sides agreed that administration was captured by special interests. Transparency demands made governance harder. So, in the 19th century, we invented a party state to manage conflicts among participants. In the 20th century, we invented an administrative state to manage these conflicts. In the late 20th century and 21st century, we’ve gutted both of those forms. That’s fine, because they did manage conflict in less democratic societies.

ISPS: And what are they doing now?

Skowronek: Of course, we still have parties and administration, but they no longer serve to ameliorate antagonisms. More to the point, we haven’t come up with anything else that might do the job. In effect, we’ve just said, “Let it rip. We’re going to gut these things, and then we’re just going to go at each other.” Ultimately, this is an elite failure. That is, those who were best positioned to see the problem were oblivious to it.

ISPS: What would a successful rewiring of the Constitution look like?

Skowronek: I don’t know. Before we get to that, we need to figure out how to even start that conversation. We have many good ideas: end gerrymandering, invest in Congress, restore the integrity of public administration, term limit the justices — but we lack a vehicle for reform that all sides might want to ride. The intellectual, professional, managerial class is as divided as everybody else. I mean, I know people say that they’re all liberals and they’re all progressives, but I don’t see it. I see it as completely divided. Look at the lawyers: legal liberals standing off against a conservative legal movement. They’re talking past each other. Meanwhile the Constitution is being rewired de facto in a way that is threatening to both constitutionalism and democracy.

ISPS: Is a constitutional convention a viable path forward, or too risky given current polarization?

Skowronek: Writing this book made me more sympathetic to Thomas Jefferson’s proposal for regular constitutional conventions to update the document. There is something to be said for thinking about institutional change holistically rather than incrementally. Adaptation is always jerry rigging the relationship between the old and the new. But I don’t see how anything productive could come out of a convention at this particular moment. In 1787, elites subordinated deep conflicts of interest to their common interest in creating a great commercial republic. I don’t see anyone subordinating their interests to a common vision today.

ISPS: What do you want readers — or even people who might not read the book — to take away from your insights?

Skowronek: It’s not about one team winning and doing everything it can to marginalize the other. It’s about figuring out how to recapture the modicum of consensus that a constitutional democracy needs if it is to work. If this Constitution no longer serves, we need to figure out what system would. Just because it worked in the past doesn’t mean it will work forever. What we need is a strong Constitution that serves a fully inclusive polity. We do not have such a constitution today. In a sense, our history should be liberating. It should remind us that we’re not stuck with the arrangements given. The Constitution doesn’t have all the answers. It never did. It survived because people reworked it, because they periodically reinvented it. But in the final analysis, we may conclude that reworking the old system yields diminishing returns. At some point, the old structure may lose all sense of integrity and essential purpose. Eventually, it may get hollowed out.