Did AI Write This Headline? Yale Provides Training to Use ChatGPT for Social Science Research

In the expansive landscape of modern research, where the complexities of human behavior meet the boundless potential of artificial intelligence, tools like ChatGPT offer a captivating avenue for social science researchers to delve deeper into the intricacies of human cognition and societal dynamics.

Does that sound interesting? Does it sound useful? Does it sound like a human wrote it?

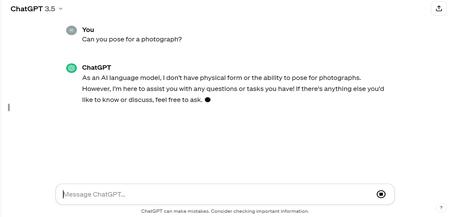

The first sentence above was written by ChatGPT 3.5, with a prompt to craft an introduction to a story for a university’s website about the potential for this popular generative AI large language model to help social science researchers in their work.

Now, to be honest, I think I could have done better. It’s a bit grandiose, for one. It’s indirect, overly long, and doesn’t grab the reader’s attention. It also deploys the clichéd phrase “delve deeper” and too many hifalutin adjectives that writers I’ve admired taught me to avoid. Words like “hifalutin,” for example.

But a recent training session sponsored by the Institution for Social and Policy Studies (ISPS), the Tobin Center for Economic Policy, and Yale’s new Data-Intensive Social Science Center (DISSC) stressed one new reality that seems unavoidable: Everyone should learn how to incorporate artificial intelligence into their work or risk getting left behind.

“Whether you like it or not, these are now imperative skills,” said Antony Ross, senior data scientist at Stanford University School of Medicine, who led the training session.

In discussions of new and evolving applications of generative AI, Ross often finds himself paraphrasing his colleague, Fei-Fei Li, the inaugural Sequoia Professor in the Computer Science Department at Stanford, and co-director of Stanford’s Human-Centered AI Institute.

“AI won’t replace people,” he said. “People who use AI will replace people who don’t.”

Trained on enormous amounts of data and able to communicate in plain language with users, generative AI tools such as ChatGPT can summarize research papers and entire fields of knowledge in seconds.

ChatGPT can translate one computer language into another. It can help anticipate trends and alter the content and tone of its responses based on the targeted audience or a persona you instruct it to adopt.

The newest subscription-based version can create diagrams and images from data inputs or text descriptions. It can teach you how to hem a dress or help prepare for a job interview. Or simply provide a sounding board to refine your thinking on any subject, even responding verbally to verbal prompts.

“Say you want to review a topic because you don’t know a lot about it, or maybe it’s been a long time since you’ve taken a class and want to make sure you have the basics,” he said. “ChatGPT is like having an expert, a student, or a colleague sitting next to you. Someone to bounce ideas off of.”

Alan Gerber, ISPS director, Sterling Professor of Political Science, and co-faculty-director of DISSC, attended the ChatGPT training. He said the session provided him with new insight into the technology’s capabilities and that ISPS would continue to organize and fund classes on AI.

“ISPS’s core mission is to support social science researchers across the university in acquiring the knowledge they need to stay at the cutting edge of their fields,” he said. “Understanding how to use AI is something every researcher now needs to know.”

Jane Hallam, a postdoctoral associate in the Yale School of the Environment, attended the DISCC training session and praised Ross’s insight and helpful examples. She had used AI to debug code and wanted to know more about how the technology could enhance her research. But she had concerns.

“Maybe I’m of the generation where we are not yet feeling that comfortable utilizing this kind of tool for any text-based output,” Hallam said, uneasy about implications for academic integrity. “But I could see its value in helping to come up with ideas for a research paper’s abstract or structure.”

Hallam said she could also see the potential for using something like ChatGPT to help create teaching materials, including test questions.

“In any case, I would definitely want to scrutinize whatever it produced before presenting it to any kind of an audience,” she said.

Ross agreed.

“I think the big thing is it should amplify what you do, not replace humans,” he said. “You should always review the output. Vet what it is giving you.”

Tools like ChatGPT draw from vast volumes of digital content to learn how to predict the next word in a sentence. They can act as experts but in reality do not comprehend what they produce. In addition, they are susceptible to producing what are known as hallucinations. They can simply make stuff up.

“I tell students that it’s like a child — it just wants to please the parent,” Ross said, adding that the most recent version of ChatGPT does not hallucinate as much as earlier versions. “If it doesn’t know the answer, it cobbles something together.”

In September, the Office of the Provost distributed guidelines to the Yale community for the use of generative AI tools, including the need to protect confidential information, adhere to academic integrity guidelines and the university’s standards of conduct, and scrutinize content for bias and inaccuracy.

Addressing that last point, Ross said that users should ask ChatGPT to cite its sources. And throughout the training session, he offered examples for how students, postdoctoral fellows, faculty members, and staff can interact with the software to craft and refine effective prompts.

He suggested starting simple and then trying various iterations to better tune the output toward specific goals. For example, users can ask for a response that assumes specific prior knowledge or none. They can ask to make something sound more exciting or more formal. They can ask to expand on a point or hit a precise word count.

Ross described the value of asking ChatGPT to tailor its replies to a particular audience. You can ask it to explain machine learning to you as if you are in the fifth grade. Or describe the internet as though you are Benjamin Franklin. You can reverse the dynamic and have it ask you questions, for example, allowing the chatbot to learn enough about your needs to help determine your best options for buying a new smartphone.

In addition, Ross encouraged attendees to have ChatGPT adopt a specific persona. You can ask it to act as a nutritionist and help evaluate your diet. You can ask it to act as an expert political scientist to summarize recent developments in the field. And then you can upload entire documents for it to analyze, summarize, compile into bullet points, organize into a table, and mine to construct multiple-choice test questions of various difficulty, complete with the correct answers.

The key, Ross said, is to constantly engage and refine. You can even have the chatbot suggest ways to refine the prompts you are feeding it.

“As you see how it is responding, you can better understand how it sees the world,” he said, noting that while ChatGPT 3.5 doesn’t know anything that has happened after September 2021, version 4.0 extends knowledge to April 2023 and can access the internet for details of more up-to-date events. “By dancing back and forth with the model, you can get a better understanding of what it can do, and it can better understand what you are really trying to achieve.”

Ron Borzekowski, director of the DISSC, plans additional training sessions on various topics. Another class on AI large language models will be held for political science researchers later this spring.

“As we continue to build the center, we want to provide more opportunities for members of our wide research community to access and understand how to best engage with the most effective tools for advancing their work,” he said. “Artificial intelligence products will certainly be among that growing list.”

Tobin Center Faculty Director Steven Berry, David Swensen Professor of Economics, and co-faculty-director of DISSC, echoed Gerber and Ross in their general enthusiasm for this fast-evolving technology.

“We surely need to grapple with the ethical and technical challenges that AI poses,” Berry said. “But we should also embrace its capacity for aiding research. I am pleased that the Tobin Center, ISPS, and DISSC can help navigate this evolving landscape.”

Reid Lifset, a research scholar and resident fellow in industrial ecology at the Yale School of the Environment, attended the training session in part to learn more about ways that ChatGPT could speed understanding of current research, by helping users search the content of multiple papers at once. He is also helping to lead a project investigating the environmental impact of the digital economy, including AI.

“There has been some research on the resources required to train these computationally intensive models,” Lifset said. “They require a lot of electricity and thus a lot of carbon emissions. Ongoing research aims to see how the coding and design of these models can be changed to become more energy efficient.”

Ross raised another concern, involving the tendency of large language models to mirror and magnify existing racial and gender biases. For example, they will likely produce images of people with light-colored skin unless otherwise prompted.

Ross said that even as AI will increasingly threaten jobs, grapple with copyright protections, and facilitate the spread of misinformation and cybercrime, it is not going away. Researchers and students can learn to guard against its risks while embracing its possibilities.

“Here’s what I think we humans often miss,” Ross said. “These AI models know trillions of answers. They’ve seen it all. For people, if you are good at what you do, you can become even better.”