When Bad Things Happen to Privileged People: Yale’s Dara Strolovitch on Crisis Politics

The Cuban Missile Crisis, the opioid crisis, the AIDS crisis, the homelessness crisis, the humanitarian crisis in Sudan, the global climate crisis, democracy in crisis … What do these all have in common?

As it turns out, that’s not an easy question.

But Institution for Social and Policy Studies (ISPS) faculty fellow Dara Strolovitch has some answers.

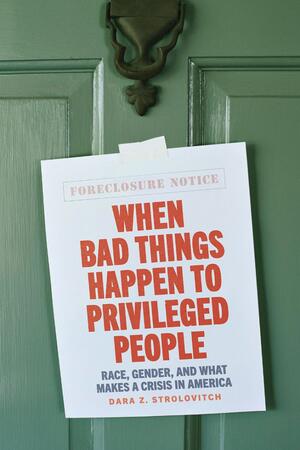

In her book, When Bad Things Happen to Privileged People: Race, Gender, and What Makes a Crisis in America, Strolovitch examines how politicians construct and exploit the idea that an event or problem is a “crisis” to justify using state power and resources to address it. As she explains, they are most likely to declare and treat something as a crisis when persistent issues that mostly impact marginalized communities begin to affect more privileged and dominant groups. The book was this year’s co-winner of the American Political Science Association’s Race, Ethnicity, and Politics’ Best Book Award.

Strolovitch is a professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies, American studies, and political science. She also co-directs the ISPS Center for the Study of Inequality with ISPS fellow and assistant professor of political science Allison Harris. We spoke to her recently about how what she calls “crisis politics” can undermine efforts to address longstanding problems that disproportionately affect marginalized groups, particularly those who experience inequities involving intersecting influences of race, class, gender, and sexuality.

ISPS: What do you mean by “crisis politics?”

Dara Strolovitch: I use that term to describe what I argue is a crucial but underexplored dynamic in the perpetuation of inequality and marginalization in the United States: the relationship between the kinds of episodic hard times — punctuated moments of difficulty or violence or economic strife that are typically understood to be crises — and the kinds of ongoing and quotidian hard times that I argue are more routine and structure the lived experiences of marginalized groups. I call this second type “non-crises.” I argue more generally that crisis politics have become a mechanism for justifying the use of state power to protect privileged groups and for justifying its retrenchment or redirection when it comes to marginalized groups.

ISPS: Is this a new term?

DS: I’m not sure. If it’s been used before, I don’t think it’s been in quite this way. I’m definitely not the first to observe that problems and hard times labeled crises play a role in the ways in which racism, misogyny, and others forms of structural inequality and marginalization are perpetrated and perpetuated. But I am trying to argue and to show empirically, perhaps in a fresh way, that we can only understand this role by thinking about those longer-term, day-to-day inequalities and injustices in relation to more punctuated, episodic hard times.

ISPS: In your book, you distinguish a “crisis” from a “non-crisis,” in an interesting way. In your telling, a non-crisis is still a crisis, right? Or even something worse: An everyday, constant state of emergency?

DS: I’m not really arguing that a non-crisis is a crisis but rather that “crisis” isn’t an objective descriptor of an event or phenomenon. And that the same political processes that construct some problems and events as crises — that is, as critical junctures deemed worthy of and remediable through government intervention and resources — also construct other similar or analogous bad things as non-crises. In this way, they are treated as natural, inevitable, immune to — and therefore not warranting — state intervention or resources.

ISPS: I see. And you show that issues falling into the first category are more likely to affect dominant or privileged groups, and those that belong to the second category are more likely to affect marginalized groups.

DS: Yes. In other words, I’m not sure if I would say non-crises are worse than so-called crises. But in some ways that might be correct. Because when political actors treat something as a crisis, part of what they’re doing is expressing some faith that it can be fixed. And part of what I argue characterizes a non-crisis is the assumption that it is outside the power of the state to fix. If we take some challenges for granted as natural parts of the normal political and economic landscape when they affect marginalized populations but treat analogous ones as solvable problems we label urgent crises when they affect dominant groups, then we’re essentially naturalizing inequalities and justifying having the state do nothing about them.

ISPS: Is this dynamic a recent phenomenon? When did crisis politics begin in the United States?

DS: The phenomenon that there are punctuated moments of political, economic, and other difficulties and crises that happen in the midst of structural inequalities and ongoing marginalization is certainly not new. But I think what’s new-ish are the ways in which the dynamics of crisis politics — and especially of crises and non-crises — have begun to function as a mode of governance in the United States.

ISPS: How far back does this go? Have politicians always used the language of crisis?

DS: I systematically analyzed the evolution of crisis language in books, newspapers, party platforms, State of the Union addresses, bills, and congressional hearings from the mid-19th century through the early 21st century. I found that until the 1950s and 60s, dominant political actors used it very rarely and mainly to refer to a narrow set of political and economic issues like wars, recessions, and conflicts in or with other countries. Economic issues were really the only domestic issues to which they applied the label during that period.

But anti-slavery abolitionists and racial justice activists began applying the language of crisis to domestic issues much earlier. For example, in 1910 the NAACP named their magazine The Crisis, in part in reference to an 1845 anti-slavery poem called “The Present Crisis.” Dominant political actors then appropriated crisis politics in the 1960s to justify using state power to address domestic issues, but they typically only did so in cases when the status quo was under threat or to justify retrenchment and punitive policies against marginalized groups.

ISPS: Do you have sense as to why racial justice activists adopted the concept of a crisis?

DS: They used it as part of an effort to reframe the ways in which Americans thought about slavery and later racial oppression and racial violence more generally. They wanted to change them from something understood as natural, inevitable, and intractable and to cast them instead as urgent policy problems facing critical junctures that could and should be remedied through state power and resources.

ISPS: Where did this concept come from?

DS: In doing so, they were drawing on its original definition as a medical term that was used to describe “the point in the progress of a disease” at which medical intervention is “decisive of recovery or death.” They wanted racism to be understood as a problem facing a crossroads at which the presence or absence of the “treatment” of state action would either lead condition for Black Americans to get better or much worse. W.E.B. Du Bois argued in the editorial he wrote for the first issue of The Crisis that racism needed to be treated as a fixable problem within the control of humans, not as the inevitable and therefore eternal product of some alleged state of nature. Later articles in the magazine would also challenge the teleological and Whiggish idea that racism would inevitably decline as Americans became enlightened. It’s the contingent outcome of human decisions and agency and can and should be fixed by humans as well.

ISPS: Specifically, within the scope of government action.

DS: Yes. It’s important to see these problems as solvable through state action and resources rather than natural or inevitable.

ISPS: And denying this relegates many enduring problems to what you call a non-crisis, right? Can you give an example contrasting how politicians have treated what you call a non-crisis and what they consider a crisis worth responding to?

DS: Sure. One set of matched cases on which I focus in the book is what came to be called the foreclosure crisis of 2007-08 alongside what I call the foreclosure non-crisis of the mid-1990s. Foreclosure rates were, by many measures, higher among Indigenous people, people of color, and sole-borrower women during the “non-crisis” in the 1990s than they would be among white and male-breadwinner households during what would come to be labeled a crisis a decade later. But data I collected by coding economic reporting, party platforms, congressional hearings, and State of the Union addresses make clear that what were essentially the same problems were treated very differently by economic reporters and dominant political actors.

ISPS: How so?

DS: At a basic level, I show that the same indicators that were described as signaling a crisis in 2007 were not described that way when they affected primarily women and people of color in the 1990s. More importantly, they normalized the high rates of subprime mortgages and foreclosures among Indigenous people, people of color, and sole-borrower women, treating them as non-crises that could not be fixed by the state.

For example, despite reams of evidence from both nonprofits and government agencies that high income Black borrowers were more likely than low-income white borrowers to be sold subprime mortgages, that racial and gender gaps in subprime lending widened as incomes increased, that women typically had better credit than men, and that it was the structure of a loan, not the characteristics of a borrower that predicted whether it would be repaid, policymakers and reporters accepted lenders’ claims that women and people of color were simply “risky” borrowers who didn’t qualify for conventional mortgages.

ISPS: Which led to the conclusion that high rates of foreclosure among women and people of color were to be expected.

DS: Yes, and it gets worse. In the book, I detail the ways in which the deregulation of lending in the 1980s had allowed a well-documented resurgence in discriminatory and extractive lending practices, many of which had been illegal for about 20 years following a wave of important fair housing and fair lending laws passed during the 1960s and 70s. This was in part to address the fact that women and people of color had been denied access to the wealth-building “gold standard” of federally insured fixed-rate mortgages that had had dominated American home lending since the government had intervened to stabilize the housing market during the Great Depression.

Rather than acknowledging the federal government’s role in gutting these laws and laying the foundation for these high rates, banks and legislators instead attributed them to perhaps unfortunate but nonetheless natural and inevitable factors about which, they claimed, the state could and should do nothing. Bad credit histories. “Life events.” Or, in the case of women, gendered stereotypes about their alleged naïveté, inexperience, or bad negotiating skills.

ISPS: I imagine the narrative changed when rates of subprime lending and foreclosures reached similarly high levels among white men in 2007?

DS: It sounds like you read my book! Yes, not only did economic reporters and dominant political actors in 2007 suddenly start describing the situation as a crisis, they also stopped blaming borrowers — at least those borrowers — for rising rates of foreclosure. Instead, they blamed the new wave of foreclosures on structural factors like the resetting of adjustable-rate mortgages and argued that the federal government could and should do something.

ISPS: OK, but wasn’t the 2007-08 financial meltdown a much bigger crisis? It was the most severe global economic upheaval since The Great Depression.

DS: Yes, and my point is not that the federal response to the foreclosures of the mid-1990s should have been at the level of the response to the later global financial crisis. I’m also not suggesting that what came to be understood as the “crisis” wasn’t extremely destructive or that homeowners who were helped by the federal response didn’t deserve it. And I’m definitely not arguing that the response was adequate, since although initial calls emphasized appropriating federal funds to help homeowners, in the end, federal money went mainly to banks, lenders, and insurers while interventions for borrowers emphasized things like borrower education, raising standards for documentation, and the prosecution of “bad apple” lenders.

But even these measures came too late to help the women, Indigenous people, and people of color who’d been losing their homes for decades because their suffering was deemed tolerable and outside the reach of the state to fix. They were also not reached by more robust responses like the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2011. And work by scholars such as Jacob Faber and Melanie Long suggests they also did almost nothing to address disparities in rates of homeownership or to mitigate inequitable, extractive, and discriminatory lending practices, which by some measures have been either unchanged or gotten worse in the years since crisis was said to have ended.

ISPS: You are saying that government action in a crisis can serve to perpetuate inequality?

DS: Yes. Even as the federal government mobilized to try to address this issue, policymakers continued to naturalize and exceptionalize the still very high rates of subprime lending and foreclosure when it came to women and people of color, essentially treating them as what I label a non-crisis within the crisis. As already accounted for by longstanding racist and misogynist assumptions and tropes and, implicitly, as the baseline conditions for how we would know that the “crisis” was over.

ISPS: And the baseline to which we would return to afterwards.

DS: Precisely. This dovetails with another feature of crisis and non-crisis. Part of how I and others argue dominant political actors decide that a crisis is over is when things go back to the status quo, to “normal” pre-crisis conditions that are often characterized by inequalities and injustices. In this case, white male heads of households were no longer at as much risk of losing their homes, but everyone else was at the same higher level of risk as they’d been before. And it was like: OK. We’re all good. Crisis over. Time for the state to move on.

ISPS: You write that the term “‘non-crisis’ is intended to describe and encompass a range of naturalized, non-spectacular, but enduring conditions such as long-term unemployment, poverty, homelessness, mass incarceration, and racialized and gendered wage disparities and violence that structure the lives and lived experiences of members of marginalized groups.” Looking at it this way, isn’t everything a crisis? Do you think it is time to retire the use of this word in political contexts?

DS: For better or worse, I don’t think we can get anyone to stop using the word. But I do think that my findings suggest that it might be helpful to question the received wisdom that seems to get smuggled in when it’s used. Ideas about what crises are and how they matter and work in politics and policy. We need to remember that a crisis is not material and self-evident thing that we can distinguish from good times but rather a dependent variable made in and by political processes. We also need to understand that we will not resolve inequalities if we do not question the assumption that things are worse, more alarming, or more solvable through state attention and resources only when they affect large and dominant groups. I also think it would be helpful to rethink the faith we seem to have that crises are generative moments of opportunity to advance social justice.

ISPS: How so?

DS: When I started working on this book, one of my first points of entry was through the important work in political science, sociology, and history that treats events like wars and recessions as both drivers of and impediments to policy change. And part of what I found were these two competing sets of ideas about what such “crises” mean for marginalized groups. Some argue that those kinds of events lead to setbacks in efforts to expand rights and resources. But there’s also a lot of faith among scholars and progressive activists that you can harness the disruptiveness — the “focusing event” of these paradigmatic crises — to open windows of opportunity through which long-standing ideas about solutions to enduring inequities can be pushed.

ISPS: Like when Rahm Emanuel was Barack Obama’s chief of staff, facing fallout from the global financial crisis when taking office in 2009. He said you should never let a serious crisis go to waste because you can do things that you didn’t think you could do before.

DS: Exactly, although I’m not sure that Emanuel had only progressive changes in mind. But yes, scholars have argued, for example, that the Great Depression of the early 20th century opened windows of opportunity for redistributive, pro-labor, anti-poverty policies. Others have argued that the Civil War and both world wars proved important for the advancement of Black civil rights, women’s suffrage, and feminism. Similar arguments were made about the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impact, that they allowed Joe Biden and Democrats in Congress to pass major legislation addressing things like climate change and expanding the child tax credit.

ISPS: So, a crisis can be an opportunity.

DS: Yes, that’s one important part of the story. But they can also redraw and reinforce lines of marginalization. For example, many of the pro-labor and redistributive measures ushered in as part of the New Deal’s response to the crisis of the Great Depression also reinforced and codified problematic racial and gender norms. Agricultural and domestic workers, for example, were excluded from both the National Labor Recovery Act and the initial Social Security program, which meant that about two thirds of Black workers, and many women workers, were not initially covered by these allegedly “universal” policies. Under the National Economy Act, a husband and wife couldn’t both work for the federal government or be employed by programs like the Works Progress Administration. That might sound “gender neutral,” but because women typically earned — and continue to earn — less than their male counterparts, many women quit, were denied, or just didn’t take those jobs.

ISPS: So not only did large portions of women and people of color not benefit from these policies, but the very policies that were supposed to address a crisis that was, in many ways, hitting them harder, actually made racial and gender inequalities worse?

DS: Right. We see these kinds of dynamics almost every time there is some kind of alleged window of opportunity attached to a crisis. The results of these windows of opportunity are also often short-lived. Most of the redistributive and economic security measures put in place at the height of the COVID pandemic, for example, were temporary and are no longer in effect, even though the problems they were addressing are far from gone.

ISPS: You argue that “increased urgency is not necessarily what makes political actors treat a problem as a crisis. Instead, whether or not a bad thing comes to be labeled and treated as a crisis is often itself a political outcome, the result of problem-definition and agenda-setting processes that make it one as political actors ‘organize it into’ politics and transform it from an ongoing, taken-for-granted, and naturalized condition into an intervention- and resource-worthy policy problem.” Given the nature of contemporary American politics, can you see a better way to galvanize action to address longstanding problems that do not often affect privileged classes?

DS: This gets back to the idea that crisis is a dependent variable. And also to your question about retiring use of the word “crisis” in political contexts. I think that what we should retire — or at least approach more skeptically — is the idea that it is during moments that are declared to be crises that we are going to achieve major advances and solve problems for good. That’s not to say that we shouldn’t try to strike while the iron is hot. Activists of course have to try to exploit windows of opportunity whenever they become available. But they also recognize that we need to address these underlying conditions.

ISPS: The conclusion of the book focuses on COVID-19 and shows that many advocates and some elected officials made clear that many of the inequalities laid bare by the pandemic were not new. Are we perhaps turning a corner in the use of crisis politics?

DS: I don’t know, but I do think that this is a step in the right direction. Rather than saying that we should “use” the crisis to address these inequalities, these leaders instead questioned the idea that we can distinguish between crisis and non-crisis and used the moment to problematize the very meaning, conditions, and desirability of the “before times.” Many activists argued explicitly that ending the COVID crisis should not mean a return to “normal” because “normal was the crisis.” For example, dozens of cities and organizations issued statements declaring that it was racism that was the “crisis.”

ISPS: So, you do not see anything inherently wrong with taking advantage of perceived, acute crises when they arrive to make incremental improvements for people who suffer more regularly?

DS: Absolutely not. We should never let the quest for the perfect be the enemy of the good or even just the better. And the book foregrounds the political actors on the ground who are doing just this work. But we should also not let our faith in the idea that crises present opportunities to allow us to lose sight of the perfect. We should not declare victory after a win and go home saying we fixed it for this one group, so see you later. Instead, we should say, “The ‘crisis’ allowed us to see and fix this one problem. Now let’s try to fix this other, maybe more entrenched, problem.” Which is often an ongoing structural condition that was there before the alleged crisis but has come to be taken as natural and immune to intervention and even treated as an indicator that things are back to “normal.”

ISPS: Pessimists might point out how little we seem to have learned from the coronavirus pandemic, noting our reported lack of preparedness for the current spread of bird flu in cows, and the growth of anti-vaccination and anti-masking sentiment in large segments of the population. There have also been backlashes to the seeming tipping point crises of the 2020 uprisings against anti-Black racism and the MeToo movement against sexual harassment and sexual violence against women. How optimistic are you that society will successfully grapple with the ideas you explore in your book?

DS: That is a hard question. One way I’ve been thinking about these questions recently is to follow those who argue that we should think less in terms of optimism and pessimism and more about trying to remain hopeful in a world in which change is not linear. If we only see the ways in which we have failed as a society to grapple with these problems, then there are few incentives to keep working on solving them. So even if we’re not optimistic that we’ll solve any single crisis or non-crisis, remaining hopeful drives us all to keep working, to keep hoping that we can do something to channel state power and resources in ways that improve people’s lives.